Kamal Swaroop’s Om Dar B Dar is a film that marks the end of the Indian New Wave in 1988. Although its prominent directors would continue making films through the ‘90s, there approach would change considerably. Both the veterans of the new wave would only make two more state sponsored films each, after which they would have to look for private funding.

Produced by the National Film Development Corporation the film was not released on its completion in 1988, but was screened across India and won the Filmfare Award for Critic’s Choice for Best Film. However its producers and the Censor Board of India had several problems largely because of their perception of the content which they found abstruse in its presentation of parallel ideas. The reception of a few sequences which consisted of religious content and violence towards an animal, a frog, went against the film’s chances of finding a release.

The film was forced to enter into the underground until it was re-discovered through VHS in the mid-90s, primarily by a group of Mumbai-based independent film-makers and curators and recently through DVD. On its rediscovery the film was describes as ‘Indian Cinema’s accident’ and for those who could not get their hands onto a copy it was termed ‘Indian Cinema’s Lochness Monster.’ Its claim to being the first Indian film to have a post modern aesthetic as well as the only one, as later attempts using similar grammar such as Sanjeev Shah’s Hun Hunshi Hunshilal not having the same complexity and often being imitations of Swaroop’s masterwork, made it qualify for ‘suggesting the possibility of an avante-garde.’

Kamal Swaroop emerged with his critically acclaimed short film Dorothy in 1974 and was pronounced heir to the throne to the film practice specific textual approach through improvisation practiced at the time at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). He went on to assist Richard Attenborough in Gandhi and more significantly Mani Kaul in what many consider to be his towering achievement Mati Maanas (1984).

His debut feature was written in the form of a story first which would constitute a film as long as eight hours. Swaroop’s student, Amit Dutta later read the entire script of the film and was very impressed. However Dutta states that the film exceeds the quality of the script. Swaroop reduced this script to a two hour version not compressing all its details but leaving them for his sequels such as Om and The Satellite City which he had planned.

The film traverses the life of Om but simultaneously portrays the transformation of the Indian State from its socialist form in the 50s to the suggestion state-sponsored media forms and their linkage to capitalism in the 80s. Swaroop suggests a class history in the Other Backward Classes (OBC) and their relationship with the upper class Brahmins through implicitly linking parts together that create a totality of (in this case) the marginalized Other.

The film begins with a boy on voice over talking about the freedom struggle and their history as being part of lower class, OBCs and their disguise as Brahmins after Om’s grandfather traveled in 1922 in the upper class Brahmin compartment of the train. Swaroop immediately suggests a narrative not forwarded by images but blocked by the voice over so that the image and sound track can acquire a life of their own free of the text. The images showing Om and his sister Gayatri at a pond in Ajmer are proof of this, whereas the reference to the year 1922 can only be ascribed to the avante garde techniques of the surrealists and Dadaists and later novelists of the noveau romanne who used a specific date randomly amongst random allocations of space and time.

Gayatri introduces herself as being born at Studio Gobar which translates into Studio Cowdung. This implicitly refers to the saying in Hindi that ‘cow is our mother.’ The intercuts to footage from the freedom struggle is the film maker’s first step towards pointing out to the audience that found footage, historical footage and often randomly placed footage shall be used to make his statements.

When Om’s father named Sankar (which means a writer, not to be confused with Lord Shiva’s name,Shankara) the audience is told immediately about Om’s death in the near future and that he would name him Om, the boy would be ‘lost from the Death’s dark gaze.’ The word ‘lost’ (lapata in Hindi) also goes back to the title of the film which translates as Om in Exile.

In the early sequences Swaroop establishes Om’s becoming from an infant to a young boy. In sequences such as a track shot where Sankar covers Om with a chaddar or bed sheet only to have Om displace it from his body begin a quest for opposing becoming with the duration of the shot. However unlike this shot (and even more prominently in Swaroop’s mentor Mani Kaul’s works) the duration of the shot itself will not be long enough to obviously stagnate the becoming of the film; not necessarily a narrative becoming but a becoming of form of violence developed alongside the progress of the film. Increasingly as the film progresses Swaroop displaces the single-shot, breaking the film into chunks anti-Eisenstein aesthetic, with a combination of shots to create this duration.

Mani Kaul’s theory on arriving at the pure image, by first calculating its elements completely and then reducing them till one arrives at an unplanned accident is most evident in the films of Yasujiro Ozu. In Ozu the matter of the elements in the frame in the form of objects and subjects, the matter in the story in the form of events as well as the matter of film in the form of image sound and their relation through editing is modified till it produces an accident through ellipse which leads to a resonance beneath the surface of the image-sound combination. Ozu would often remake his own films making minute changes such as minute events in the film (matter of the narrative) or location (matter in the image) as well as changing the filmstock between black and white and colour and specifically using colour beyond its contours of psychological realism to create a surface with the same intensity in which a new tension is created every time the maker cuts to a new space or repeats the same space.

Already in Uski Roti Kaul had begun his use of scales in the form of camera distances much like Ozu, who would often use 3-4 camera distances. Kaul used 7 distances which according to Rajadhyaksha were ‘1.4 feet to 2.8 feet to 4 feet to 7 feet to 15 feet and so on.’ Kaul mentions that the objective was to ‘discover a group of distances and repeat them’ which ‘facilitated the allusions to past sequences.’ These allow to create a system where different ‘fragments’ are created and the differences between these fragments are much more important than the similarities.

At the same time it could be claimed that Ozu’s repetition of space is used by virtually all film makers today. Even if different spaces are used unlike the use of certain devices (e.g. repetitive camera distances in the case of Kaul) bring the viewer back to repetition and increasingly with the arrival of the post modern any-space whatever the spaces do not repeat at fixed intervals or in the form of a pattern. These devices help the film gain a quality of ‘becoming-motion’ and becoming-time which Deleuze observes as the qualities of Ozu’s film. Talking about his debut work Swaroop says ‘the images keep repeating in different shapes. And adhering to a musical system of returning again and again.. (a)nd arriving at a ‘sam’.

Swaroop’s use of Hindi is unique. In One Thousand Plateus , Deleuze and Guattari talk about the language-tree becoming where the origins of language are found in its roots and if language is to be used beyond its centered meaning oriented capacity in variable ways, the roots must be rhizomatic so that the divergence and convergence of roots suggests the arrival or precedence of centering. Swaroop much like Mani Kaul is thinking of both Hindi literature in hands of authors like Nirala who use doubling in their adjectives and adverbs as well as the 9th century text Dhwanyaloka to think of the flow of their words and their suggestive potential with respect to their meaning.

Dhwanyaloka is about Dhvani as being the essence of poetry. Dhvani itself is the pure suggestion produced by exploitation and exhaustion of every element in poetry mainly the alankara or embellishment, guna, subject which it qualifies usually resulting in a positive or negative quality, riti, styles of theatre and vritti, styles of poetry. The three fundamental kinds of dhwani are vastu dhwani (Dhvani of subject), Alankar Dhvani (Dhvani of embellishment through figure of speech) and the superior most Rasa Dhvani (Dhvani of rasa or pure mood). Cinema is somewhere forced to be between vastu dhwani or dhvani of subject also meaning subject of matter as film is matter and somewhere the pure rasa theory. Ozu is perhaps the only master of dhvani film as the suggestive matter of the corridors,buildings and objects transform into mood usually in his later films after the death of Chishu Ryu.

Talking about the use of language Swaroop mentions his attempt to create sentences which were not total in themselves and would become ‘generative’ and would generate another meaning altogether. The objective is to create endless possibilities to the text, a characteristic also present in Somadeva’s text Katha Sarita Sagar which has the format of a story within a story often interconnected without causality. Language in the film is constructed in the form of riddles, questions, clues and directives so that the audience cannot ‘consume’ the film but realizes its potential. This is dissimilar to genre cinema which often seems to have the same objective other than the fact that genre focuses on the image itself, its stylization and form to relate it to a number of ideas whereas Swaroop irons out the image often by de-aestheticizing it and ironing it out to Kaul’s ‘single image reduced to its minimal’ and then working on the sound and the text to create multiplicities of information.

In this was Swaroop is able to handle his references to Gandhi, Nehru, television and marginalized politics through information and integrating it into a political machine, what Deleuze and Guattari call the war machine which does not have war as its objective. Swaroop repeats his devices, but never his spaces to create pure deterretorialized spaces which do not occupy space but point to the space before or after it in the necessary succession. In this way the deterrotorialized spaces lead to a movement beneath the surface of the image which is ‘erected’ as in Kafka through the process of its filming and location. Swaroop relates this ‘location’ to its mythic equivalent (the myth of Pushkar) and the relation of the filmed location to the mythic location through the process of an accident which is unknown.

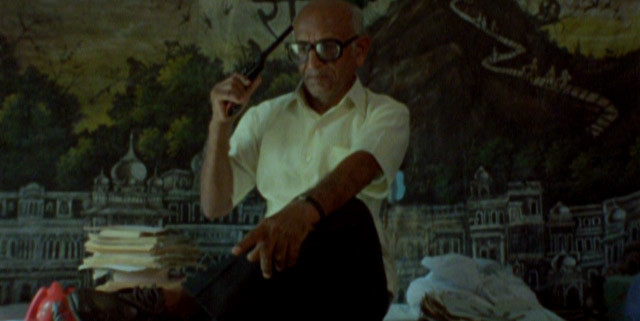

The relationship between Jagdeesh and Gayatri has a sophistication in its use of film form. Both communicate only through the radio and writing letters. Their talks are largely about women’s lib through the story of Parvati, Lord Shiva’s partner, are about she may be able to climb Mt. Kailasa in the Himalayas without Shiva’s help. Jagdish attempts to liberate her through teaching her how to cycle and then by having pre-marital sex with her, after which she automatically has a bob cut, a fad among women in the ‘80s to demonstrate their indifference towards emasculated society. Jagdish on the other hand is a good for nothing unable to find a job for himself and target of Babuji Sankar’s anger when he tries Babuji’s tricks on his own daughter. Babuji employs him in office to give him a part time job. At the end of the film Jagdish is shown returning from Dubai where he has done well for himself.

The remarkable sequence following Babuji’s acceptance of labeling his nephews as OBCs to fit the special quota for jobs with false papers consists of the brass band song which influenced Swaroop’s colleagues and continues to do so at Rupert Murdoch’s music television channel, Channel [V] as well as Swaroop’s student in the mainstream, Anurag Kashyap particularly in the choices made in filming of the song Emotional Attyachar in Dev D (2009). Swaroop begins the song with an image comprising of a man dressed like Elvis singing what sounds like the words of a love song combined with the first six or seven alphabets of the English language. Swaroop wanted to examine the effects of the ‘copulation’ between English and Hindi which according to him produced the spastic advertisements that are consumed by the middle-class milleau. Swaroop follows this with a cut to a dancer representing what would be Bombay Cinema’s disco dancer in the 70s with a red hair band dancing and singing looking straight into the camera. Although Swaroop may have meant this as a direct reference to Bombay Cinema and their filming of songs where actors often look directly into the camera abruptly without mediation or aestheticizing, this image can also be thought as a movement image ‘crystallized’ out of the duration of the progression of the film to mark a point where the movement in the story (the abrupt song), the movement of the actor and image are one. Swaroop invites Jagdish into the song through a zoom in to frame him in the background and a person’s collar in the foreground imitating some of the devices Bresson used in fragmenting the image through creating tensions between matter especially at the edges of the frame. At the end of the song sequence when Jagdish pulls of Sankar’s trick of pulling the hair band and running, Babuji on the voice over rebukes Jagdish with the background music of a chase in a Hindi film, and then cuts to images of Jagdish’s pockets and hands removing and giving the hairband, a direct reference to Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959) whose form Swaroop is employing in his process of breaking film up into chunks and not through Eisensteinian montage.

Much like Mani Kaul’s best sequences, Swaroop works around the notion of interiority as being the root to the films controlled,even false temporality, much like the notion of being in tune or sur in Hindustani music that can only be achieved through rigorous introspection that is at the same time completely taught.

Swaroop’s attempt to use film to recreate his specific circumstances while growing up in Pushkar is matched by his awareness of film form and its ability to take up different specific forms even with similar content. The film is through the eyes of Om, Swaroop’s alter-ego. At the same time Swaroop is very aware of the fact that he in order to create film form he has to maintain objectivity. A strange situation arises: the film talks about the exploitation of lower class dalits while its own detachment from society to create a junk-machine, in between Warhol and Bresson, can only find its traditions in an endless tradition of upper class Brahminical questioning.

The story has its mythological basis in the story of Lord Bramha, who in Hindu mythology represents being that manifests through his breath, who promised to raise the town of Pushkar, where Swaroop grew up to the position of heaven but at the last minute ‘broke his promise.’ Swaroop uses the mythological story very much within the logic of Brahmanism to represent the ‘pathos of the boy called Om.’

Swaroop uses a remarkably inventive soundtrack to create a non-sensorial logic to film. Whereas the image is often mundane and the camera wandering, the soundtrack has so many layers to it that one is forced to notice the veneer of pop-art like abstraction beneath which exists a tradition of classicism. Take the sequence at the terrace party. Swaroop splits the action across two terraces and the party reaches a high point when the scientist crosses over from one terrace to the other. The terrace party on the same day as the landing on the moon creates a Dadaist form of sorts. Swaroop juxtaposes middle-class morality and logics of sprawling with radio voice overs reporting the landing on the moon. In this way he subverts the logic of an obviously first world event to attempt to recognize a very specific third world modernity and the film form it creates. The sounds include middle class housewives talking about taking a trip to the moon to spend a vacation, the first lady ‘Miss Chanchalta’ meaning Miss Innocence that was the first to wear a sleeveless nighty representing a freeing of female sexuality and the rather masculine sounding talks of man reaching the moon, science and this being played of the proposal of getting the scientist married to the daughter of the house. Later when the same daughter is confronted with Phoolkumari freshly arrived from Bombay (now Mumbai) she asks her as to whether women will be able to climb Mount Everest referring to the earlier discussion between Jagdish and Gayatri

Om’s adolescence is represented by the remarkable classroom sequence to represent the boys masterbating in the class. Swaroop uses imagery such as the on-off of the projector-bulb,the frogs representing women until a cut to a daily with a skimpily clad teenager, representing modernity is made followed by a shot of the woman being held by a hand. In an interview Swaroop talks about how a man’s genetelia represents his own feminine aspect, if not a woman itself. The act of masterbating is played against this dichotomy of masculine and feminine that also is part of the purush-prakriti or masculine-nature concept of Hindu mythology with the feminine representing nature. Swaroop equates this natural movement to the movement of machines both cinematic and those part of the production cycle that Om will be confronted with later and become a part of, even killed at the expense of.

Om’s journey from the classroom to Prethkund is shown in a succession of remarkable sequences, where he starts occupying the space in between home, the classroom and the playground: the well in the playground. This directly refers to the story of Bhaktaprahlad and his killing of his father King Kashyapa in the form of Lord Vishnu disguised as a tiger known as Narsimha, in a space neither inside nor outside. Reference to the Bhakta Prahlad story are also evident in the student works of Amit Dutta.

Om constitutes a nomad who cannot be categorized fitting into Heisenberg’s uncertainity principle of energizing a particle through gazing at it. Such a scientific approach negates any kind of feminist reading with reference to gaze or scopophilia. The approach to the actor/character is precisely through the gaze. Being critical of gaze would be like being critical of the apparatus set up for an experiment and in a sense being irrelevant to the experiment itself.

The entrance of Phoolkumari, who introduces herself as being from Bombay and reading Times of India to denote her modernity, which Habermas points out as being an era where human beings constitute a center, and class, addresses Om’s developing sexuality by splitting the space that already existing between Jagdish and Gaytri and Om and Babuji. Phool is now pushed in the midst of nature where the absence of civilization transforms her into a witch and gives full bloom to her already active sexuality. Jagdish at one point is convinced that she is Rosemary Marlowe, the pornographic writer while Phool introduces herself as an actress in religious sitcoms. Phoolkumari is played by perhaps Indian television’s most important actress Anita Kanwar, who played Lajoji in Hum Log, and was typecast by advertisers and television channels as being the docile woman who stood for traditional values. What followed was a split between the television actor’s roles and the products that they sold in between. A remarkable example of this was B.R. Chopra’s kitsch production of the Hindu epic, The Ramayana in between which the actress who played Sita sold detergent powder. This split is represented by Phool who states that she was typecast as a religious deity and the only choice she had out of it was to become a cabaret dancer, a sacral-profane split different from the sacral-businesswoman split that constitutes the Ramayana example and would become a mercantile logic for the right wing Indian party, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP).

Phool enters Om and Babuji’s dream and also convinces Om to wear dark glares which gave James Bond peace of mind as well. The dark glasses, both a reference to the fashion of kitsch Bollywood heroes and blind men, makes Om a sitting duck in the hands of town and city based capitalists. Phool being from the city is only an agent to aid them in this logic of exploitation.

The premise of Om Dar B Dar is political, although the film is not about politics. The film indicates a politically appropriated mythology that reinforces the caste system and the maintenance of status quo in favour of upper castes. Om, a lower caste boy whose family the audience is told in the opening minutes by Om on the voice over ‘has been dressing up like (upper caste) Brahmins since three generations’ has a father who is a lower caste fortune teller, who is swayed by the upper caste Phoolkumari who changes the relations between the members of the family through her agenda. A significant sequence is where Phool gives Om a pair of glares with which she claims ‘even James Bond got peace.’ The glares prevent Om from seeing his own situations as a lower caste boy who is going to be exploited. Om’s affiliation with tadpoles is Swaroop’s signature method of using totems from ancient texts and using them as transformative devices to suggest becomings beneath the surface of the film. The frogs indicate both the lower caste characters that have been shrunk to fit into the whole of society. According to Swaroop these are also indicative of the coming of television and its shrinkage of screen size, which are mediocre in all aspects of scale in comparison to the large scales of cinema.

Swaroop juxtaposes his concern for cinema and television with the politics of Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayana and how the television series became a political agenda with the Ram Janmabhoomi (Lord Ram’s birthplace) at the place of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, played up by Lal Krishna Advani of the Bhartiya Janata Party. The film ending of the film where Om performs Lord Brahma’s descent to Pushkar followed by his being worshipped as a deity,also denotes his ritualistic form of sacrifice. Om’s friend Atlas, who we hear on the soundtrack and never see except in long shots, convinces him that for him that whereas those above water are holding their breaths on land, for him the normal state is to hold his breath under water. For him to protest, he would have to breath underwater, which would kill him, by exploding his lungs. In short under the pretense of protest the ritual is a well designed plan to murder him. Swaroop is commenting on the mechanism by which political parties intervene the process of making a space holy, by juxtaposing it with the only indication of death itself in the present, the dead body, which is also treated as holy in the Hindu religion. Those on land hold their breath to watch the sacrifice of a lower caste for the pretense of religiosity. Swaroop is both underlining the practice of the ritual as a unique act outside the logic of banal day to day living as well as being critical of it. Ghatak talked of the cinema as being like a ritual, where the lights are shut off, the projector shut on, and then the film projected as an act outside of day to day life.

The purpose of this piece is to present Om Dar-B-Dar as an attempt at constructing a documentary so that filming on location outdoes/undoes any attempt at constructing narrative. The narrative is projected onto the location space. The location space i.e. the city of Ajmer is the apparatus for Swaroop to ‘realize’ his script bu undoing the script. While making the film Swaroop’s reference was to construct ‘ a narrative that resembled a documentary or a documentary that resembled a narrative.’ Swaroop was not particularly confirmed on whether the succession of ideas ‘made sense’ but was interested in projecting an organism of ideas in the Deleuzean sense onto the city of Pushkar.In this way the aerial shots of the city intercut at different points in the film define both the topology and limits of the apparatus as well as the transformation of the city-object that forms the basis of the film.

During my interaction with Kamal Swaroop on 14th May,2011, the artist begun by talking about his lack of interest in ‘illustrating’ the scenario. The illustration of scenario could make it an ‘actors film’ with performativity being the other side of the Deleuzean machine that fundamentally comprised of the eight hour long script (narrative).In this way the film tried to capture the ‘accumulated spirit’ of the city of Ajmer as well as its limits which consisted of the matter in the image i.e. actors, props and locations and the endless ideas, all of which would not be captured on film. In this way the film itself, according to Swaroop, would document the spirit of the narrative space of Ajmer as well as become an iconic motif of Swaroop’s emotional connect with the city.

This spirit can be relted to the presence of matter which relates back to monetary capital, both the capital that is required to produce the film as well as the capital present in the matter within the imag.e The presence of the spirit is the hidden face of capital that creates violence. The relationship between the Panda at Prethkund as well as Om is the relationship between capitalist and labourer. The decentered and nomadic spirit of Pushkar is the basis of the cultural capital that is then transformed to emotional capital through Swaroop’s personal experiences. In Kamal Swaroop’s words the mise en scene, a spatialized process became unbroken through the whole of the spiritual aspect of the film, which is nothing but the location space of Pushkar.

However the spirit becomes actualized at Prethkund as the water contains money i.e. the tax of the common people who come to pay their respects at the holy spot. Swaroop thought of the schizophrenic split in Pushkar as belonging either to mad people or to spirits. The fact that the pond is located in the arid desert of Rajasthan made the landscape of the desert a space for the acquatic spirits as well as the organic body of water. In this way Swaroop creates an ‘accumulation’ of the spirit much like the temporal succession of images in time create an accumulation of the matter in the frame.

Swaroop juxtaposed this fluid schizophrenia with a discourse around the controlled nature of the space of Prethkund. Om is led to the lake of Prethkund through the coin. Swaroop was impressed by the image of Chinese frogs with coins in their mouths. Om is led into Prethkund through the dream. The coin itself has two sides, one is its material aspects, the coin’s physicality whereas the other side to the coin is that they proliferate in water, after people have thrown them there, and coexist with spirits or mad people that co exist in the water.

The discourse on control is present in the early sequences as well. Jagdish meets an astrologer who tells him how he can control the woman he loves. The notion of control according to Swaroop, was a discourse on class and caste mobility i.e. on how lower and upper castes in a fairly rigid society can obtain interchangeable positions. The picking of a hair to control Gayatri can also be compared with the act of lifting a fate line from the palms to alter the logic of a particular sequence. Similarly Swaroop constructs a mise en scene where a new image, a new object will transform the logic of the space. The film therefore becomes a constantly transforming logic that is defined by either a song or a statement that creates the constantly transforming object. This constantly changing object can only be formed by i) giving due importance to the ‘qualitative’ nature of the location space and ii) through having more ideas than can be ‘illustrated’, so as to have the idea of the film as something very different from the realized images.

To hold this plethora of ideas Swaroop inserts literature at two levels. The first level is the level of myth where objects are taken out of ‘classical’ literature be it the classical Hindu texts, the story omnibus Katha Sarit Sagar or the idea of the Guinness book of World Records. The second layer is the level of popular culture through kitschy literature as well as from cutouts and stories from newspapers and magazines. This creates a constantly changing logic of matter in the film to underline through difference, the repeating radio jingles, top angle shots of Pushkar as if taken through a microscope. A combination of difference and repetition in the shots of the house, where the same space creates different surfaces through spaces, so that the interiority of the house creates the deterretorialized feel of a prison film.

In this way Swaroop hopes to transform a real space i.e. the city of Pushkar through imposing artificial fiction on its limits. Swaroop employs the Deleuzean split between the virtual and the actual to create a set of game like circumstances where the actuality will either accept or reject the ‘virtuality’ of the artificial narrative. The role of the film maker is simply to record the transformation of this object. Swaroop compares this transformation with an erection of a mall that will transform the qualitative nature of the landscape around it.

The case of Phoolkumari, a witch who comes to Pushkar to complete her portfolio from the Babuji’s dating service. Her command over the English language makes her the ideal choice for Sankar’s burgeoning marriage business. She is consequently hired as a typist. Later on Babujia accuses her of stealing the diamonds that were hidden in the heel of Om’s shoe. In Brechtian fashion, Babuji shouts ‘check her-top to bottom’, but Phool curses him with a game theory like anagram. According to it if Phool is not a liar Sankar cannot cross the threshold of his house or else he will die. Contrarily if Phool is indeed a liar, she will die. Swaroop claimed that he wanted to contrast the transforming geography of the city with the arrival of television and the motor car with the transforming geography of the house once Sankar has been cursed and can no longer leave the house. In this way he believed he was transforming the space through a faith in black magic that gave new meaning to Swaroop’s discourse on politics, religion and the notion of wealth.

Swaroop in an interview mentions as to how he found the actor as a hurdle in trying to film pure objects. He instead was interested in ‘recording’ the process of his struggle with objects such as cycles and cars to capture a ‘dignity and grace’ in the actor which he thought was ‘acting’ instead of a ‘pretense.’

Swaroop’s engagement with shadows throughout the film trace back to his own belief in the materialization of an idea in an image through its ‘reality’ or its shadow. In this way shadows become Deleuzean reterretorializations of the image that define the Bergsonian split between the actual and the virtual. According to Swaroop this transformation of ideas into images was much like a rewriting process. In addition to this one could add that the rewriting is precisely the sense of documentation that the film allocates in its unique approach that destroys the dictatorial nature of the concept-script. Through documentation the script idea is destroyed through a purification of the script so as to remove the decorative ‘illustrative’ elements.

According to Swaroop the two sides of a purified image include the non-causal dream image as well as its most skeletal image the image of the cycle. Swaroop is also in dialogue with Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh, the cult left wing author in his pursuit of portraying a lower middle class angst and the sense of explosion it causes with external causal processes like class mobility and a new dynamics in the politics.

Swaroop is also dealing with his roots in science practice at the Indian Science Research Organization (ISRO).Swaroop, who tried to combine art and literature by reading Russian folk tales through science uses the city of Ajmer and later Pushkar as the scientific ‘apparatus’ for his artificial construct. In addition to this Swaroop engages with a ‘pure memory image’ much like in Welles Citizen Kane (1941) where the notion of Rosebud conflicts with the visual nature of the entire film. In this way Swaroop hopes to construct a notion of time which according to him comes from a (re) structuring of the themes of pain and death in order to capture a residue of time which is the pure memory image.

Arguably the most memorable images are those of the classroom where the boys masturbate while the teacher is away. The scene is set with Atlas continuing to stay on his cycle and the boys enacting a Deleuzean becoming of a frog through a Kafkaesque metamorphosis in the classroom. Swaroop builds on the notion of the skeletal image by showing a skeleton in the classroom and relating the different parts of the skeleton to the different body parts that the boys recollect in the classroom. Om’s nose is the centering of these body parts as his nose is the physiological aspect of his greatest achievement: that he is able to hold his breath underwater for long periods of time. It is also a recording device for pain: both the pain that Om feels when the cricket ball hits him as well as the pain of living ‘life’ as it were, so that he is forced to tell Babuji that his ‘nak’ or nose is coming in the way of his sight. This is again testimony to Swaroop’s objective of constructing pain through the unraveling of the riddle film.

The classroom sequences also go back to Swaroop’s play with words as the class also depicts the class divide between the capitalist and the worker and between teacher and student.